The Beauty of Winter

Winter in El Calafate, Argentina, 2016

Every year I wonder whether Scotland’s winters are too cold for me. On the worst days, it’s a blistering cold, the type that I feel in my bones. My vegetable box, dominated now by earth-covered beets, potatoes, carrots and turnips, lacks colour and vitality. I make borscht, often, heaped with dill and parsley and lemon juice, to use what I have, and to stay warm.

Harvest means very little to most people living in places of great abundance. Now, all winter, we can buy out-of-season fruits, imported from South Africa or Spain, to satisfy our need for colour and sweetness. My winter vegetable box reminds that in the past, the cold months were a time of scarcity. Our ancestors would have had to get through it with their preserves, ferments, and the hardier harvest fruits. Eventually the pantry emptied. Those must have been cold dark days of hunger. How did they get through it, year after year? Knowledge of the natural cycles reassured that the great cold would not go on forever. Spring’s promise of renewal is encoded in so many different festivals and time-markers, from the the Gaelic Imbolc – celebrating the first milk – to the Sugar Moon of March, a time when the Ojibwe tapped maple trees to extract precious amber syrup.

Yet recently, speaking with Ojibwe scholars and authors Anton Treuer and Wendy Geniusz, I was reminded that winter is not merely a time to get through. For many it is a sacred time, when the spirits are most present. For many Indigenous communities across North America, including the Ojibwe, winter is a time to slow down, come together, and tell stories, living and spirited stories, which can only be told ceremonially, to treat the spirits with utmost respect.

Such reverence and ritual might sound unfamiliar, but I was reminded of the way we, in much of the UK, gather by the fire in December and tell ghost stories. Our spirits are not the same as the ones that exist in the Anishinaabe cosmology. We often see them more as metaphors, terrifying but not real. But our ghosts are in their own way sacred, crisis apparitions, omens, and channels for us to explore our insecurities, traumas, and our fears around mortality. They remind us, like Scrooge’s visitations from the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future, about how we are living, and help set us back on course. And sometimes they feel more real: Samhain, Halloween and Day of the Dead mark the passage to that time – sorry for the cliché – when the veil between worlds becomes thin. It’s thin all winter, as we hunker down, try to stay warm, and look every day upon a dead or dormant world. Come Christmas Eve, it is said, we might even be able to speak with other animals.

And so in some ways my body fears winter, the agony of leaving the shower, the inability to get warm, the hunger. Except: there are these frostbitten mornings, sat on the top of a double-decker bus, peering through condensation, at the pink sky rising above the grey stone, the park silvery in the morning light. There is sanctity in the cold, dark mornings. In strangers gathering in a warm cafe, relieved by each others’ company. Walks with friends in the drizzle, crisp leaves underfoot, our hands clasping hot cups of coffee, tracing old memories, birthing new ones, trying to weave together loose threads to create narrative.

When the landscape is stripped bare we have an opportunity to see ourselves more clearly, too. Late at night, I sit beneath a blanket, penning poems, catching up with my reading, and entering the minds of authors long since dead. I re-read War and Peace as if it were a sacred text and maybe it is. Writes Leo Tolstoy, ‘If everyone fought for their own convictions there would be no war.’ We have been told to blame the system, to wring our hands, to cry, to carry a hopelessness that aids corrupt power, but it’s a false spell. Certainly, we should distrust billionaire hoarders, particularly CEOs of big insurance companies who make a living off people’s ill health, but we shouldn’t wait for the sleeping king under the mountain to save us. We are the consumers who demand goods beyond the bare necessities, our own personal vehicles, throwaway clothes, laptops and phones made from cheap labour, for the forests to be cleared for soy for animal feed, animal flesh, animal’s milk, for things mined from the earth, our convenient plastic that takes hundreds of years to decompose. The system is born from individuals, and can be dismantled by us, too.

Winter in Seoul, South Korea, 2017

Winter in Glen Clova, Scotland, 2012

Winter in Alabama, 2014

Winter in Shimla, India, 2015

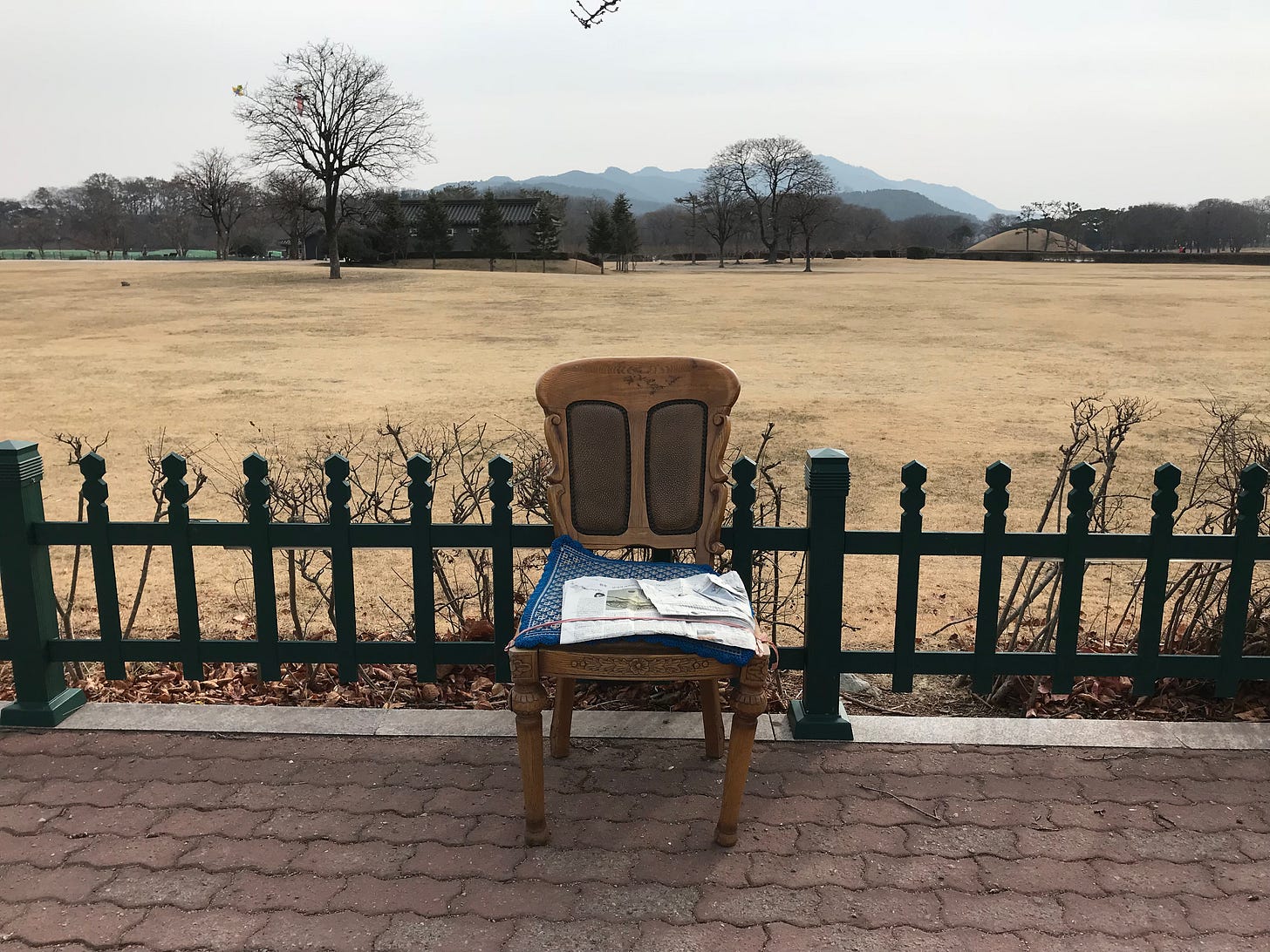

Winter in Gyeongju, South Korea, 2018

Winter in Gyeongju, South Korea, 2018